Thoreau came away from his final visit to Maine with another important realization. It was his understanding of the vital need to preserve the great history and rich culture of Maine’s Native people. As we push away from the shore of the 150th anniversary of the publication of “The Maine Woods,” we can all be grateful that Thoreau’s vision was shared by so many others in the years and decades that followed.

Today the Penobscot’s history and traditions, as well as those of Maine’s three other Native American tribes—the Maliseet, Micmac and Passamaquoddy—are alive and vibrant and waiting for your discovery. Known collectively as The Wabanaki, or “People of the Dawnland,” Maine’s Native people continue to honor their culture, traditions and connection with the natural world.

Every year, the Wabanaki ways come to full bloom once again at special events and festivals throughout the state. A great way to begin your own journey with the Wabanaki is a visit to the Abbe Museum in downtown Bar Harbor and at Sieur de Monts Spring in Acadia National Park. The Abbe is one of the first museums built in the state and the only one dedicated exclusively to the history and heritage of Maine’s Native people. It’s easy to imagine a young Henry David Thoreau marveling at the Abbe’s archeological collections, with stone artifacts dating as far back as 10,000 years.

For more recent manifestations of Wabanaki culture, you’re invited to attend the Maine Native American Festival and Basketmakers Market held each summer in Bar Harbor at the College of the Atlantic. This is Maine’s largest gathering of Native American artists and features the celebrated Native American Arts Market. Exceptional craftwork and authenticity are the hallmarks of this unique opportunity to learn about contemporary Native American arts and their historical roots and to take a piece of it home.

In the Kennebec Valley Region, the perfectly named town of Unity is home to the annual Common Ground Country Fair. Make sure to visit the Native American arts and education area for exquisitely crafted basketry and jewelry, educational talks and traditional music and dances.

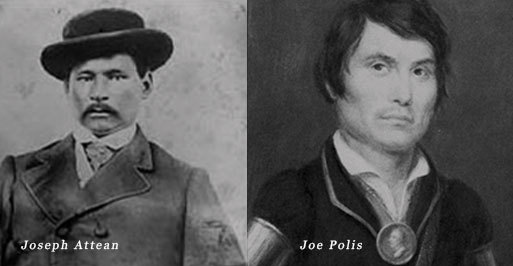

Of course, you can get a taste of the ancient ways of the Wabanaki, and a oneness with nature and the Great Spirit just by stepping outside a tent at the first light of dawn in any of Maine’s vast and timeless natural areas. Put a canoe in one of our pristine lakes or rivers, close your eyes for a moment and imagine Joseph Attean or Joe Polis right there behind you with wisdom and stories to share. Or maybe you can even see—in the canoe up ahead—a man with a pencil and a journal and eyes wide open to whatever happens next.